A journey to the bottom of the world to improve global connectivity

July 13, 2020

Swarm is fortunate to have the sage support of the National Science Foundation (NSF): through its Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, Dr. Sara Spangelo and I (co-founders of Swarm) visited McMurdo Station Antarctica to install a custom made satellite ground station to support our satellite network deployment.

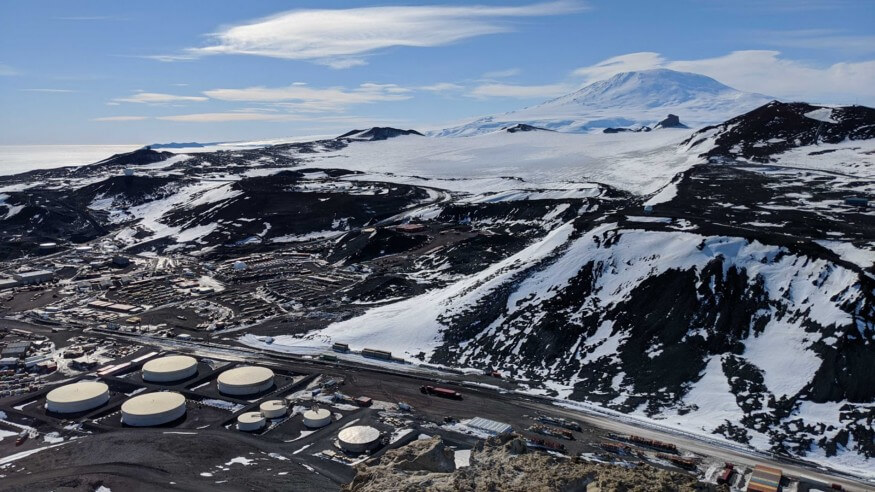

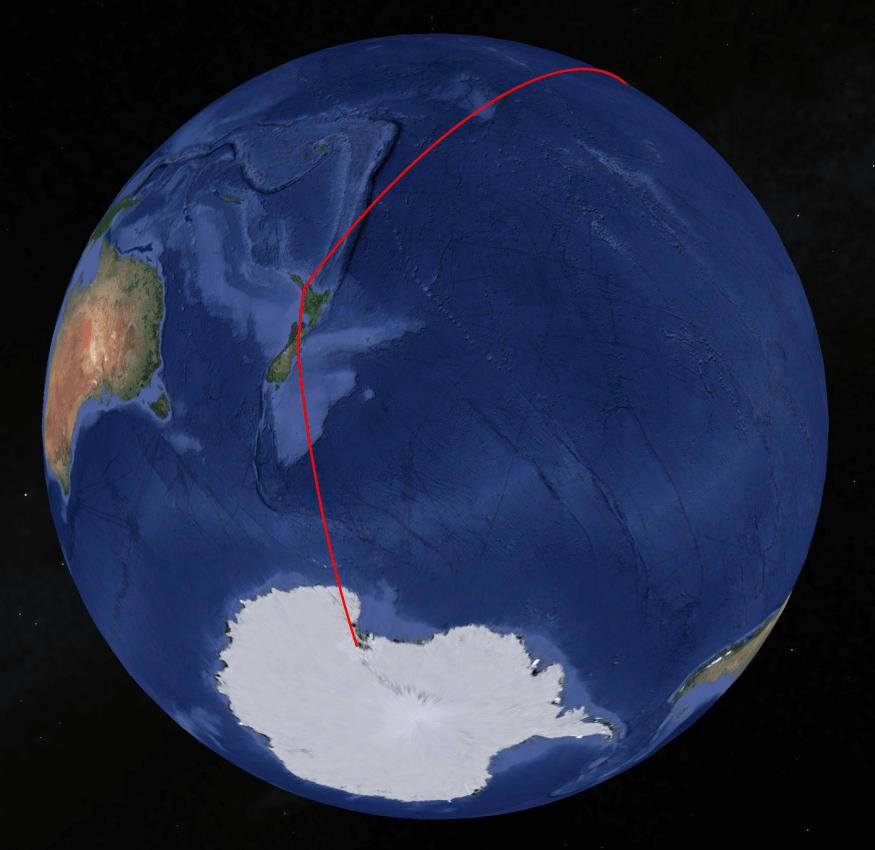

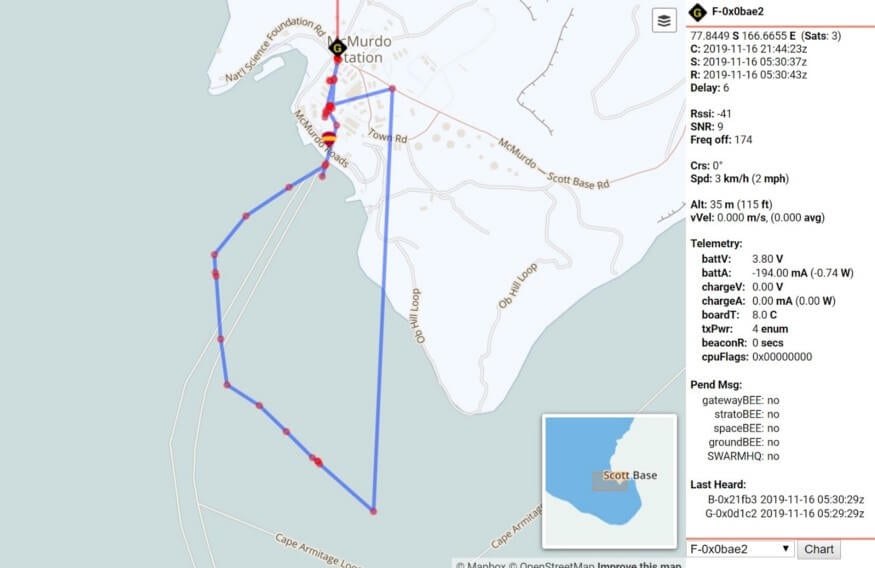

McMurdo, located at -77.8500, 166.6667, is run by the NSF and is one of the most Southern outposts before the South pole, and is located on an island surrounded by semi-permanent sea ice near the shore of Antarctica. This is a particularly optimal location for a ground station because the Swarm satellites are in polar orbits, passing over the South (and North) poles every 94 minutes. Any IoT data or messages collected by the Swarm satellites during the orbit can be downloaded once the satellite passes over a pole, or McMurdo Station. Existing satellite connectivity at McMurdo and all southern bases on Antarctica is very poor: we were excited to meet engineers and scientists who felt this pain and wanted to learn more about Swarm and the connectivity solutions we could offer. At certain times of day, there is a 4 hour communications blackout between McMurdo Station and South Pole bases, making scientific and operations communication extremely difficult.

On our journey to Antarctica, we first flew to Christchurch, New Zealand, where we went through training and extreme clothing outfitting to make sure we were prepared for the low temperatures “on ice.” Our most notable equipment was the large red Canadian Goose parka (rated down to -60C) and inflatable “bunny boots” for walking around on the ice. The flight South from New Zealand was aboard a C-17 military cargo aircraft, run and operated by the U.S. Air Force. In addition to passengers,a large Volvo front-end loader for operations at the base was onboard, “freshies” (fresh fruits and vegetables, since no plants can grow at the base), and pallets of scientific equipment from universities and national laboratories.

Arriving in McMurdo was an intense experience: we landed on a permanent ice runway, walked out of the plane with our parkas, large bunny boots, and were immediately hit with a blast of frigid polar air in near white-out conditions. Our ground transport waiting for us on the ice was an arctic land vehicle with comically large tires, thick insulated walls and survival gear inside. It took us on a one hour journey to McMurdo Station, the permanently inhabited U.S. base.

Upon arrival at McMurdo, we went through orientation training (which seemed to be a combination of survival and Space Camp training!) and then were allowed to navigate around the base on our own. It felt like a small town, complete with a dining hall, hospital, two bars, three work-out areas, a recreation hall, and dorm rooms. We discovered that the cafeteria was even better than expected at our first dinner, and we enjoyed some of the “freshies”, which had arrived on our flight.

Installing Swarm’s Ground Station

The following morning we woke up before 7am (but the sun had never really set so it was already quite bright) to attend an additional briefing, hosted by the NSF Science team. Our fellow scientists shared their planned experiments and NSF staff described their operations and logistics roles. Temperatures were frigid on the second day as we set out, -30C air temperature with a -45C windchill. And this was summer down here!

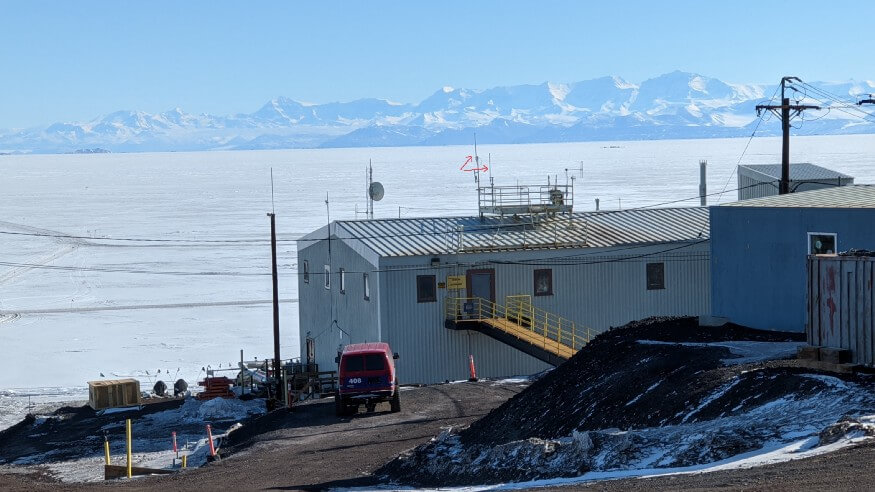

We headed to the “Comms Building” and got to work trying to connect to IP ports and deploy our antennas on the roof. We had custom designed and constructed our antennas for the -60C temperatures and had previously tested them in a wind tunnel at up to 200 mph winds. (We were told that 100 MPH gusts were not uncommon during the Antarctic winter months.) We met several members of the NSF communications team, who are tasked with keeping the scientific data and personnel data flowing on the base. The entire base of 1,000 members (during the summer) share a single connection of 17 Mbps (the equivalent of a single cell phone connection). The comms team “antenna riggers”, who’s full time job is to install antennas at McMurdo station, assisted in the deployment of the antennas on the Comms building roof. The Swarm antennas have a 360-degree uninterrupted view of the horizons which is great for communicating with the Swarm satellites in our polar sun-synchronous orbits and look out over the Ross Sea Ice Shelf.

Once we sorted out all the equipment on the first day, I went to the roof with the riggers, while one of our engineers back home in Utah, Alan, debugged the ground station connectivity remotely. By lunchtime we had one antenna installed on the roof and both ground stations (one primary, and one backup) on the network, although we were still dealing with VPN port access permissions. By 4pm we had the systems installed, and were waiting for the IP issue to be resolved, which would require support from someone currently at the South Pole. The 4–8hr comms blackout was a difficult operational task to deal with during equipment set up and debugging. Sara kept warm in the comms building, program managed the rest of the installation, photo documented the process and procedures, and maintained communication with Alan back home by Slack and email.

On the third day, the weather turned out to be quite nice and resulted in blue, sunny skies at a balmy temperature of -7 C. The sunny day allowed us to dodge from building to building without our Polar Parkas on.

Exploring the Ross Ice Shelf

We spent the following days diagnosing the network connectivity, and testing the newly installed ground station with a prototype “Tracker” device, a handheld Swarm satellite modem, that we brought with us. We took the Tracker for a spin out on the ice using “Ice Bikes” from base, filed an off-base “exercise plan,” and rode out onto the Ross Ice Shelf on a very strict designated vehicle/walking/bike path from McMurdo Station to Scott Base. Out on the Ross Ice Shelf, the views were incredible, gazing out at the Olympus range through crystal clear air (nearly 0% humidity).

In the remaining time “on ice,” we attended additional safety training briefings, exercised by running around base, hiked up “Observation Hill” for a panoramic view of McMurdo Station, the historic Discovery Hut that was built in 1901, and Mount Erebus, the southernmost active Volcano on Earth.

Antarctica is intense

The environment in Antarctica is intense, and can turn to dangerous or deadly conditions for anyone trapped away from base unprepared. The air temperature during our visit varied from -10C to -30C, with a wind chill down to -45C. I grew up in Wisconsin, and Sara in Winnipeg, and we thought it would be a breeze to cope well with the extreme “summer” temperatures. Antarctica proved to be far more challenging than the Northern Midwest. There were two days where it was difficult to breath without a face covering, and any exposed skin was at risk of frost-nip and frost-bite within minutes. The humidity level was basically zero, which meant that everything metallic gave you a shock at each doorknob grab. It was surprising that my laptop survived the multiple shocks per day. With limited communications to the outside world, psychological and physical isolation, specialized clothing required, low temperatures, and dry rocky conditions, it felt like we were on the surface of the Moon or Mars. In fact, a good number of the NASA psychological studies of isolated small groups come from various “winter-over” periods at McMurdo and South Pole bases.

As we deploy several dozen ground stations around the Earth for Swarm’s satellite communications, we envision a world where satellite data connectivity is so wide-spread and at such a low cost, that any person or sensor can have a communications device at any point on Earth at all times. We plan to make that dream a reality in 2020 as we build out our network and launch the first of Swarm’s planned communications constellations around the Earth. Perhaps one day, we will even launch some of our satellites to lunar orbit and bring communications to an astronaut working in a nearby crater at “New McMurdo Station” on the Moon.

In a future post, I will talk about our results from deploying the McMurdo ground station, our user ground modem research, and the remote science applications they help unlock for the research community. Stay tuned!

Dr. Benjamin Longmier

Swarm Co-Founder and CTO